The Japanification of the US

News

|

Posted 24/02/2020

|

16466

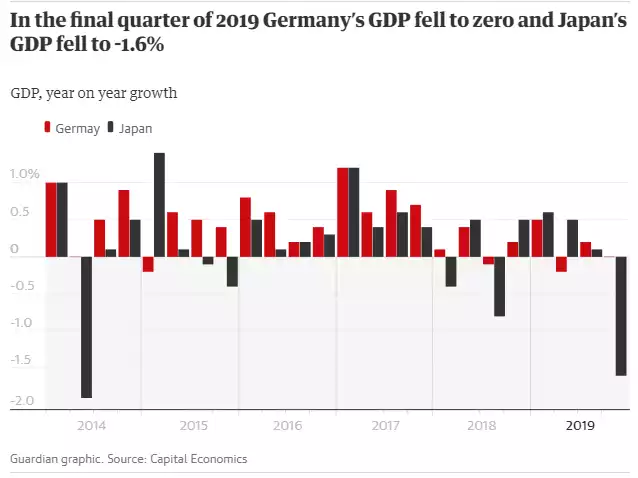

Last week saw news break that Japan, the world’s 3rd largest economy, suffered its worst quarter of economic growth since 2014, shrinking 1.6% or the equivalents of a 6.3% annualised contraction. This came at the same time as Germany, Europe’s largest economy, printed a zero GDP in Q4 after flirting either side of it in Q2 and 3. Notably Q4 was prior to Coronavirus seeing many predicting 2 consecutive negative quarters are looking likely for Japan and hence a technical recession.

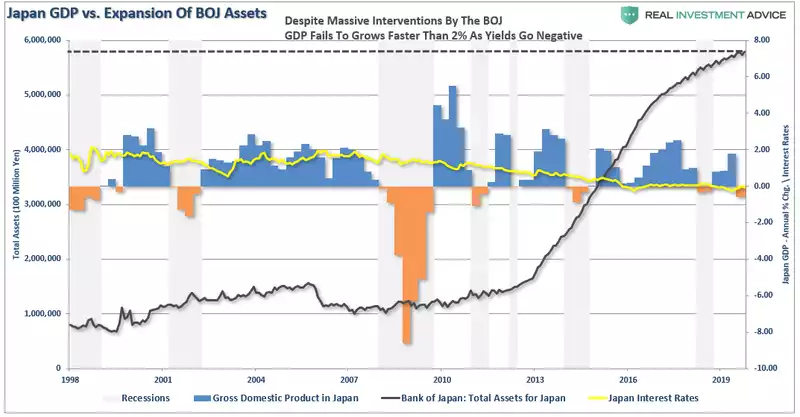

However, it is the Japanese example that has some analysts most concerned about the growing parallels with the US. Like the US, since the GFC Japan has undertaken a QE program to try and reflate their economy. On a relative bases that program has been over triple the size of the US Fed’s program. Like the US, it has done wonders inflating asset bubbles but little to achieve real economic growth across the real economy. Unlike the US Fed, the BoJ not only bought bonds with all this freshly printed money, it bought an extraordinary amount of shares through ETF’s to the point where the central bank owns 80% of the ETF markets, as well as corporate bonds. As you can see below, the results are anything but great:

As you can see from the yellow line, Japan has twice now entered negative interest rate territory and remains there now. Lance Roberts of Real Investment Advice explains why this is relevant and important for the US:

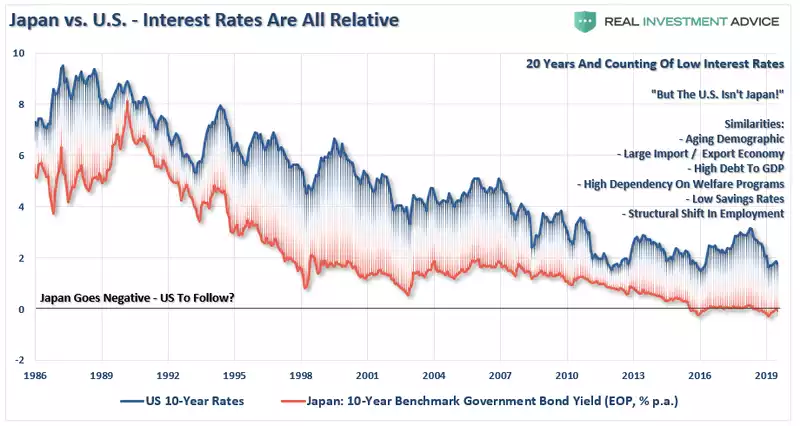

“The U.S., like Japan, is caught in an ongoing ‘liquidity trap’ where maintaining ultra-low interest rates are the key to sustaining an economic pulse. The unintended consequence of such actions, as we are witnessing in the U.S. currently, is the battle with deflationary pressures. The lower interest rates go – the less economic return that can be generated. An ultra-low interest rate environment, contrary to mainstream thought, has a negative impact on making productive investments, and risk begins to outweigh the potential return.

Most importantly, while there are many calling for an end of the ‘Great Bond Bull Market,’ this is unlikely the case. As shown in the chart below, interest rates are relative globally. Rates can’t increase in one country while a majority of economies are pushing negative rates. As has been the case over the last 30-years, so goes Japan, so goes the U.S.”

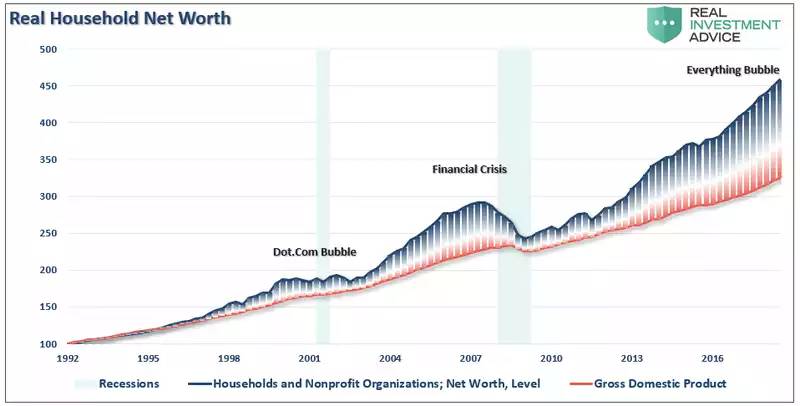

Inflating sharemarkets does little to improve an economy with around 90% of the population seeing little to no benefit from rising share prices. Research has shown that apart from QE1 which saw a 1.6:1 ratio of QE to Share price (coming off a low base and QE being ‘new’), since then and including the current ‘notQE’ Repo program, the Fed has seen a perfect 1:1 ratio of effectiveness of expansion of their balance sheet to increase in the S&P500. And so the enriching Wall St not Main St mantra is perfect. As we have written many times, this not only is ineffective in improving the economy, it is creating a growing and dangerous social divide. i.e. most of the blue below is held by the top 10% with that 10% holding all the inflated assets and the rest holding the debt and economic hardship.

As noted in the 3rd chart above, the US and Japan share not only the same response but also many demographic and economic challenges. Whilst Japan’s zero immigration policy accentuates its aging demographic problem to one of the worst in the world, it is certainly not alone as the boomers all start to retire. All around the western world we are seeing this aging population becoming a net drag on savings, net cost to tax payers, and forced sellers of equities at a time the market is sensitive to it. Japan has been struggling with this and its languishing economic growth now for decades. That unleashing a world leading program of QE and negative interest rates has had little effect should sound a clear warning to the Fed and others. At some point an economy, a real economy, simply can’t be effectively stimulated with more or cheap money. Roberts summarises where we are now nicely:

“While another $2-4 Trillion in QE might indeed be successful in keeping the bubble inflated for a while longer, there is a limit to the ability to continue pulling forward future consumption to stimulate economic activity. In other words, there are only so many autos, houses, etc., which can be purchased within a given cycle. There is evidence the cycle peak has been reached.

If the effectiveness of rate reductions and QE are diminished due to the reasons detailed herein, the subsequent destruction to the “wealth effect” will be larger than currently imagined. The Fed’s biggest fear is finding themselves powerless to offset the negative impacts of the next recession.

If more “QE” works, great.

But as investors, with our retirement savings at risk, what if it doesn’t.”