Silver’s Flash Crash & The Real World Problems Low Prices Create

News

|

Posted 10/07/2017

|

8844

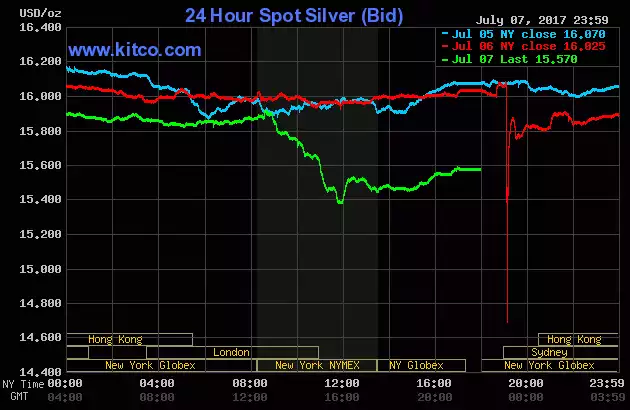

It is difficult to write on any other topic this morning than the “mysterious” silver flash crash that we saw just after 9am AET on Saturday. This saw the September silver contract on the Nymex exchange fall by 11% in minutes only to quickly recover the bulk of that decline as shown in the red plot below.

In response, even main-stream CNBC author Evelyn Cheng wrote that “computer-driven trading has gone too far”, noting that “like most other recent flash crashes, the drop in silver occurred outside of New York business hours and in the early hours of Asian market operations”.

Chris Grams, senior director of corporate communications at CME stated that “our markets worked as designed, with velocity logic pausing the market for 10 seconds at 18:06, allowing liquidity to come back into the market”. But why should such “logic” be required and why is this now considered to be normal or “as designed”?

Labelled by the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) as a nondescript “glitch”, we look at the situation a little more deeply. We’re not so accepting of “glitches” when it comes to aircraft or the safety harness on a roller coaster so why then should the fundamental stability of markets or the industries supplying them with commodities be viewed any differently? As we’ll see, there are real world consequences for the price of Silver being so low.

With the help of Vince Lanci, senior partner at Echobay Partners, let’s have a look at what likely happened over the weekend. Vince suggests that trading algorithms operating on thinly traded markets where on-book stops rest and where there’s less continuous order flow will start “fishing”. To paraphrase, he goes on to explain

“When you have three or four big algorithms that find a stop they start competing with each other and they [prices] start to snowball lower; selling in front of each other, buying from each other so that you get this negative snowball effect lower. What ends up happening is (and this is where the glitch comes in) when you have a HFT [high frequency trading] algorithm selling so fast that the order book of the exchange can’t keep refreshing its buy orders, you get markets that are trading at 14.34 when the exchange hasn’t had a chance to put in its 14.62 bid by Joe Smith. The result is what you call a glitch”.

Vince concludes that these trading algorithms, now such an inherent component of markets, have become “predatory in an exchange sense” in that the HFT computers are faster than the actual exchange. To be clear, when asked directly whether silver is a buy to invest in, Vince simply replies “absolutely”.

The relationship between algorithms and “glitches” as an idea supported by Kitco senior analyst Jim Wyckoff who said that this type of thing will “probably continue to happen on a sporadic basis, especially now with the speed of electronic trading”.

Trading algorithms aside however, these low prices have palpable effects in the real world as beautifully articulated by Jason Burack over the weekend.

Jason describes how many miners have cut costs to the bone and by doing so, are potentially ruining the mines long term. “Mines can run at a loss for a little while but if they have a bad balance sheet and a lot of debt due and they don’t have a lot of cash on the balance sheet, there could be huge problems for the miner”.

Currently there is some capital available through debt or equity but it’s a punitive penalty rate. Jason uses Coeur D’alene mining is an example of a major minor in trouble at current silver prices.

Coeur produces 16 million ounces a year of silver. As a senior silver producer they’ve also been adding a lot of gold production because “once you get up to that level of annual silver production it’s really hard to routinely keep all of your revenues in silver”.

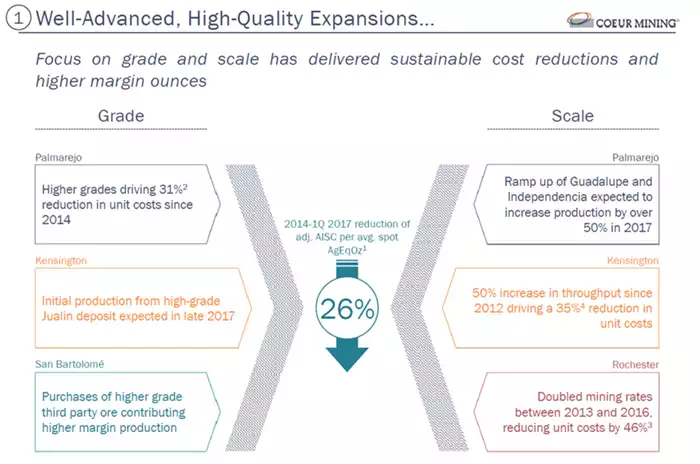

Coeur D’alene’s investor presentation to Goldman Sachs dated June 20th demonstrates how aggressive cost cutting has become. Slide 5 (displayed below for convenience) indicates that from 2014 to the first quarter of 2017 costs were reduced by 26%. That is an impressive amount but notable is how long it took them to do that especially when considering the silver bear market started in 2011. Jason states that “mines are complicated and capital intensive. You can’t cut 26% costs in a mine overnight. There are a lot of moving parts and there are dozens of things that can go wrong”.

Currently, Coeur D’alene isn’t managing $1 an ounce margin and that puts their balance sheet in peril.

Jason continues by saying that “we’re at a silver price now below $16 and that has a lot of dangerous real world consequences. Hccla and Coeur D’alene have cleaned up their balance sheets but they’re by no means in great financial shape”.

In fact between Coeur and Hccla, at current silver prices there could be a lot more than 30 million ounces of silver production a year in major trouble and this puts the supply side at further risk in an already high physical demand environment. As they say, the solution to low prices is low prices.

Jason suggests that even viewed as a speculation, buying 10 or 100 ounce silver bars and holding them for 2 or 3 years as a trade alone could see a 30 to 50% appreciation. This supports our recent discussion of the difference between core holdings and speculative allocations and at these sale prices, the asymmetric opportunities are hard to ignore.

If you are interested in learning more, Ainslie Bullion will be presenting at the NUU Understanding Money Conference on Saturday 26th August 2017. Suitable for all, this conference will exhibit a range of presenters on a number of topics from the definition of money, its past and future, cryptocurrencies and of course gold as the oldest form of money. We look forward to seeing you there.