Dealing With Debt – Inflation, Default & Gold

News

|

Posted 20/05/2020

|

23913

A large tailwind for gold, silver and bitcoin at the moment is the massive amount of debt being added to the massive amount of debt added since the GFC which was caused by a massive amount of debt. Spoiler alert, today we are going to talk a bit about debt.

Debt itself is not a bad thing, if it is productive debt. It’s how the world works. You borrow money at X%, do something productive with that money creating economic growth of Y% and pay back your loan plus X% on the basis that is less than Y%. This of course all falls apart when Y < X and you need to borrow more to pay X because Y is not enough.

There have therefore been essentially just 3 ways to reduce debt. Do as you probably set out and get a productive return higher than your P&I payments, or hope for high inflation that sees, ideally, both your asset rise in value and/or your income to pay off the loan, or if none of that works, default.

Most of what is driving gold, silver and bitcoin presently is the combination of surging government debt off deficit funded fiscal stimulus programs combined with their central bank colleagues rampantly printing money and suppressing interest rates to lure you in to more debt and spur on inflation to achieve that second debt reducing objective. Simplistically they are on one hand amassing more debt, and on the other hand desperately trying to raise inflation to deal with it.

However as we reported last week, we are likely headed first into deflationary crisis before all the current and inevitable doubled down money printing during the deflation crisis causes epic inflation on the other side. That then puts us squarely before the default option or a ‘debt jubilee’ as it becomes at the sovereign level. If the latter happens gold is off to the moon.

UBS Global Wealth Management’s Chief Economist Paul Donovan debunks the pure inflation option thesis for governments as simply not true. He summarises as follows (and we will include his full report below today’s news for those wanting to dive deeper):

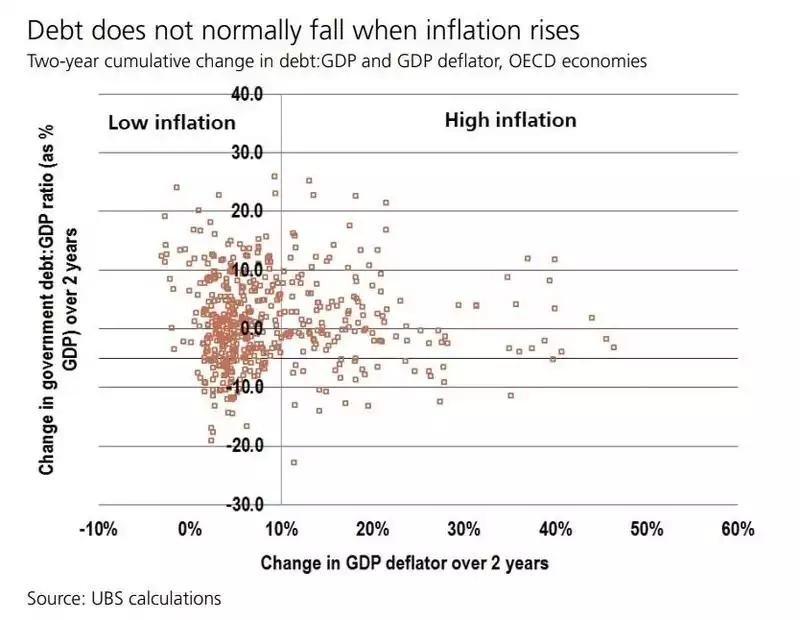

- Government debt to GDP ratios rarely fall in periods of high inflation. Since the 1970s, debt reduction has almost always taken place with low inflation.

- Government spending is strongly linked to inflation. This can be formal (as with the US social security budget) or just because the government is a consumer in the market place and must pay the higher price.

- If bond investors are hit with unexpected, high inflation they are unlikely to be happy. When this has happened in the past, investors have demanded an insurance against future inflation shocks. This risk premium raises the real cost of borrowing for a government, making it difficult to lower debt ratios over time.

- Financial repression—a form of taxation where savers are forced to hold bonds—can be combined with inflation to reduce debt ratios. However, this hurts companies and threatens growth. Financial repression without inflation is a more effective solution. Governments are likely to use this method in the future.”

So what are the implications for gold, silver and bitcoin investors? The government and central bank’s fixation of using fiscal and monetary stimulus to avoid a depression seem to have no happy ending in this crisis.

- Few would or could argue that in this environment we will productively ‘earn’ our way out of the deepest debt hole in history. It took a World War to do that last time which might explain some of the sabre rattling at the moment.

- Before we can even hope to see any inflation we are likely to enter the worst deflationary period of our lifetime. About the only certainty in that period will be governments desperately trying to turn that around through more debt accumulating stimulus. That would inevitably drive money into gold, silver and bitcoin even further.

- Once deflation turns to strong and possibly uncontainable inflation, as it inevitably must after that much money is injected into the system, if what UBS spells out is repeated, we have a double win of gold’s traditionally excellent performance in high inflation environments, combined with the effects of a forced ‘financial repression’.

The inevitable turn to inflation is not a fringe view either. From Bloomberg:

“Hedge fund luminaries including Paul Singer, David Einhorn, and Crispin Odey are among those bullish on gold, according to recent letters to investors. So are large asset managers like Blackrock Inc. and Newton Investment Management.

“Gold is the only escape from global monetising,” Odey wrote. Gold futures were the third-largest position held by his flagship Odey European Inc. fund at the end of March. “In the short term, the money will be made on the inflation bet.””

As if speaking directly to UBS’s fourth dot point:

““We expect policymakers to target and applaud mid-single digit inflation, which, combined with interest rate suppression, will be the only way to outgrow the mounting debts,” Einhorn’s Greenlight Capital argued in a letter to investors.”

And

““It’s almost inevitable that there will be a fiscal tailwind for gold -- when markets wake up to the scale of the stimulus,” agrees Catherine Doyle at Newton Investment Management.”

These are all Wall Street heavyweights not fringe gold bugs. Rarely have we seen an environment where gold, silver and bitcoin appear to have such a clear each-way-bet to outperform.

Full UBS report:

“Inflation is a complex topic. Entire books can be written about it. One of the myths that exist about inflation is that governments can easily inflate away their debt levels. In the modern world, government debt-to-GDP ratios rarely fall significantly in periods of high inflation. Since the 1970s, successful debt reduction has almost always taken place with low inflation.

What inflation should we use?

When talking about debt, it is income inflation not price inflation that matters. Income inflation makes it easier to pay down debt. If a person has a fixed rate mortgage that is three times their income, and their wages rise three times, then it is a lot easier to pay off the mortgage. Their debt to income ratio goes from 300% to 100%. Their income has "inflated" away their debt ratio.

For governments, the inflation rate that matters is also income inflation. How much a government's tax revenue is growing tells you how easily they can pay down debt. This is why government debt is normally measured by the debt-to-GDP ratio. Because governments can tax the income of the domestic economy, the growth of the domestic economy is a quick way of measuring how easily debt can be managed.

The big difference between people and governments is that people are expected to repay their debt at the end of the mortgage. Governments are not. Governments need to borrow again and again. It is that fact that makes it so difficult for governments to inflate away their debt. It creates two problems.

Problem one – deficits grow with inflation

Government spending is increasingly tied to inflation. In the 1970s the US began to formally link social security payments to consumer price inflation. Japan's pension payments have formally been tied to inflation since the 1970s as well. Even if there is not a formal tie, the government is a consumer in the market just like individuals. If prices go up, the consumer pays more. If building costs go up, then governments will pay more to build infrastructure, for example.

So while a government's tax revenues will tend to increase with inflation, a significant part of government spending will also increase with inflation. This means that deficits will increase with inflation. Inflation is unlikely to help reduce the amount of money spent each year. This makes it harder to reduce the overall debt level. But the fact that deficits rise with inflation does not stop debt reduction. It just makes it harder. The real damage is done by the second problem—the reaction of bond markets.

Problem two – bond markets' punishment offsets inflation's help

Inflation itself is not a problem for bond investors. If investors were sure inflation will be 10% a year for ten years, they would happily buy bonds that covered the inflation cost. Bond yields would be 11.5%, guaranteeing a 1.5% real rate of return. But investors cannot be sure inflation will be 10% a year for ten years. Inflation uncertainty is a problem. If you think inflation is going to be 1% and it turns out to be 10% that is very bad news for the investor.

In reality, inflation cannot be kept absolutely stable. But if there is an expectation that it will not move much, and tend to get back to trend over time, investors are happy. If inflation starts to rise rapidly, that happiness disappears. Investors start demanding some kind of insurance against the unpredictable nature of inflation. Thus, if inflation jumps from 3% to 6% investors will want payment. They will want a real yield (in normal times, perhaps 1.5%). They will want payment for the inflation (6%). They will also want an insurance premium in case inflation does not turn out to be 6%, but comes in at 8% or 10%. That insurance is known as inflation uncertainty risk. It is worth somewhere between 1% and 1.5%.

In other words, if governments try to inflate their way out of debt, bond markets will demand a price. And because when a bond matures a new bond takes its place, that inflation uncertainty risk will eventually be charged for all the outstanding debt. It is not just new debt that costs government more. Eventually the existing debt will cost more money too.

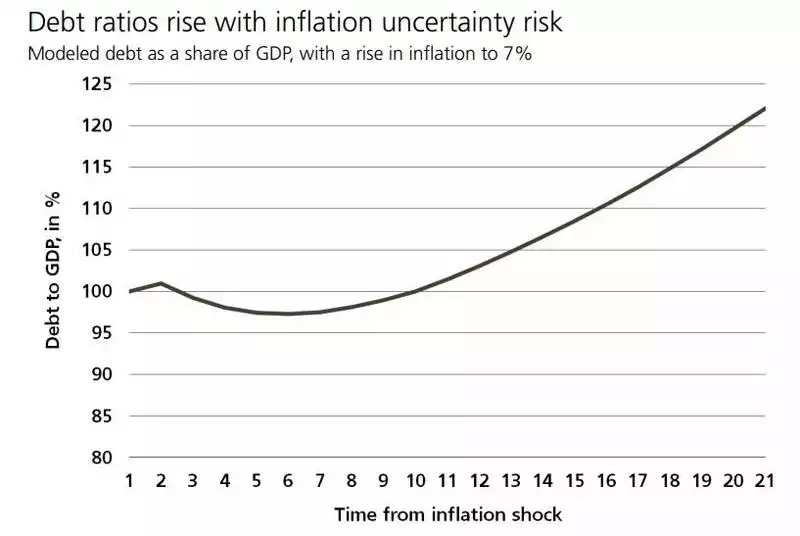

This chart is a simulation of what inflation uncertainty risk will do. This shows that inflation reduces debt ratios a little in the short term. As more and more bonds need to be refinanced, the inflation uncertainty risk raises the cost of borrowing for a larger and larger proportion of the debt. The debt-to-GDP ratio starts to rise, in spite of the inflation.

This chart shows the two-year change in government debt plotted against the two-year change in inflation, for each OECD country. The data covers 1970 to 2019, where available. Nearly all the debt reductions take place when inflation is low (below 5% per year). High inflation and debt reduction almost never take place at the same time.

Repression and inflation

Governments are likely to try to reduce debt levels after the virus by taxation. There is one particular form of tax that is likely to be popular— financial repression. Financial repression is when investors are forced to hold government bonds, at a lower yield than they would freely accept. Investors have been forced to give up some of the yield that they want to the government. Giving up money to the government is a tax, however much it may be disguised.

Financial repression has been effective in cutting debt in the past. Financial repression also means that bond markets cannot punish governments for inflation (at least, not as easily). Bond yields are forced lower under financial repression. So why not mix repression and inflation together?

While this mix would cut debt ratios, it would come at quite a high price. Financial repression normally only applies to government bonds. The inflation uncertainty risk would apply to corporate bonds. Without financial repression to help, the real cost of borrowing for companies would rise, hurting economic growth.

For a government it makes more sense to tax savers through financial repression, while keeping inflation moderate. Adding inflation does not reduce debt in the long term.”