BIS Warning of Paradoxical Frothy Markets

News

|

Posted 05/12/2017

|

7330

BIS, the Bank for International Settlements, is often referred to as the central banks’ central bank. They (now) famously were one of the few such bodies that warned of the pending repercussions of the risky lending levels that triggered the GFC just before it unfolded and are warning we are in similar territory now.

In their latest quarterly global economic review BIS are again voicing a clear warning of the current situation of central bank tightening (from the US at least) “paradoxically” leading or coinciding with increased risk taking in what they called a “frothy” market – both shares and bonds. From Bloomberg:

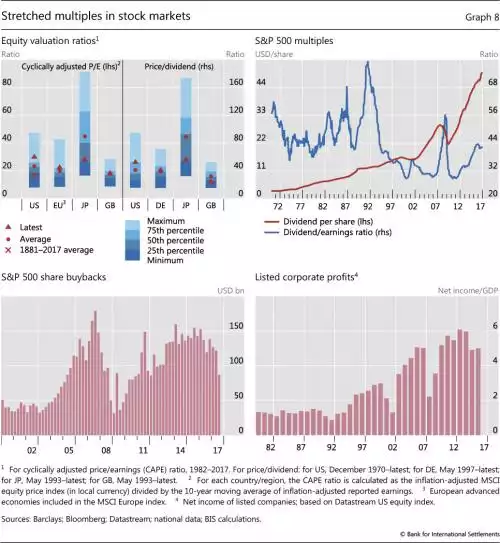

“The BIS weighed in on the debate just days after Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said a prolonged bull market across stocks, bonds and credit left its measure of average valuation at the highest since 1900. Stock prices are above historical averages and U.S. companies may struggle to continue their pace of dividend growth, the BIS said in its quarterly review on Sunday.”

So why the paradox of a market acting like the easing is still in place when the Fed in particular is tightening? Essentially, they say, because the market doesn’t entirely believe it, and are betting on ‘central banks to the rescue’ should things turn. They are also believe the very gradual implementation we’ve seen of talk-talk-talk-act to date means there will be no shocks. But that, they warn, is dangerous:

“Less appreciated perhaps, the very mix of gradualism and predictability may also have played a role. The pace of tightening has slowed across episodes, and it is now expected to be the slowest on record. And, scorched by the outsize reaction in 1994 - not to mention the "taper tantrum" in 2013 - the central bank has made every effort to prepare markets and to indicate that it will continue to move slowly. Indeed, today's experience is reminiscent of the repeated reassurance of the 2000s' "measured pace", except that the adjustment has been, if anything, even more telegraphed. If gradualism comforts market participants that tighter policy will not derail the economy or upset asset markets, predictability compresses risk premia. This can foster higher leverage and risk-taking. By the same token, any sense that central banks will not remain on the sidelines should market tensions arise simply reinforces those incentives. Against this backdrop, easier financial conditions look less surprising.”

One symptom of this easy environment is the sheer scale of share buybacks and big dividends propping up prices at the expense of sustainable business practice. From Bloomberg:

“Stock valuations may drop when the dividend and buyback frenzy eases. In the U.S., companies increased their share of net income paid out in dividends by more than half over the last five years as buybacks swelled. The dividend payout ratio is back to the relatively high levels of the 1970s and therefore may be reaching an “upper bound,” the BIS said.

“When and if interest rates begin to rise, corporates may have the incentive to tilt their capital structure back to equity, or at least to reduce stock repurchases, which could raise further questions about stock market valuations,” the report said.”

Indeed… check out these charts from the BIS report….

Their conclusion:

“First, and most obvious, the jury is still out. There is a sense in which the tightening has not really begun. The vulnerabilities that have built around the globe during the unusually long period of unusually low interest rates have not gone away. As underlined in this Quarterly Review's special features, high debt levels, in both domestic and foreign currency, are still there. And so are frothy valuations, in turn underpinned by low government bond yields - the benchmark for the pricing of all assets. What's more, the longer the risk-taking continues, the higher the underlying balance sheet exposures may become. Short-run calm comes at the expense of possible long-run turbulence.

Second, a deeper question is what defines an effective tightening. Can a tightening be considered effective if financial conditions unambiguously ease? And, if the answer is "no", what should central banks do? In an era in which gradualism and predictability are becoming the norm, these questions are likely to grow more pressing.”