Farewell Glenn Stevens & The ‘Cost’ of QE

News

|

Posted 06/09/2016

|

5523

Today RBA governor Glenn Stevens gives his final interest rate decision before handing over the reigns. Since he started in 2008 he has cut rates from 7.25% to the current record low of 1.5% as the world came, and still comes to terms with the GFC, what started it and how the central banks’ response threatens another of a much bigger scale.

Whilst the RBA has not gone down the quantitative easing (QE) path of other nations, desperately printing money to spur on growth and inflation, we are getting periously close to the line in the sand where they have said they would do so, as we reported here. Few, however, think he will lower rates today, taking us just 0.25% from that magic 1%. Greg Canavan of The Daily Reckoning summed it up nicely:

“It would be folly to fire another interest rate shot in a war we simply cannot win. The RBA would be much better off conserving what little ammo they have, using it when they really need it.

As I’ve pointed out many times before, our dollar is strong because Chinese stimulus at the start of the year put a rocket under the iron ore price, which has a big bearing on Australia’s finances. While the perception of the Chinese economy remains strong, there will be a strong bid for the Aussie dollar.

Cutting rates by another 25 basis points will do little to dissuade foreigners from buying the dollar, especially when the options are to hold euros or yen (and having to pay fees to do so).

But another rate cut will impact bank margins, punish savers and knock confidence in an already fragile economy.”

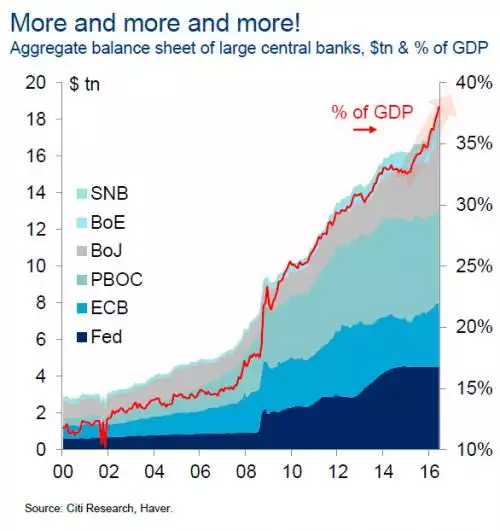

That said, the market still expects more cuts soon, just not today. As for Australia joining the QE game before we get to that 1%, the following graph by Citi bank should send shivers up your spine if you are ‘all in’ in financial markets. It shows the balance sheets of the 6 major central banks in the world. If you recall, QE is when the central bank buys assets with freshly printed money (those assets sit on their balance sheet). The US led the way buying only US Treasuries. More recently the likes of Japan, the ECB and the Swiss have been buying nearly anything they can get. We’ve reported previously how the BoJ is now a top 10 shareholder in over 200 of the Nikkei’s 225 companies. So look at the following graph in the context of ‘what if’ these central banks can no longer prop up markets anymore. What happens when purchases (much of that debt in the form of bonds) to the tune of 40% of global GDP either stop or stop working. The description ‘Ponzi scheme’ is often used in describing this unprecedented economic set up, and it’s hard to argue.

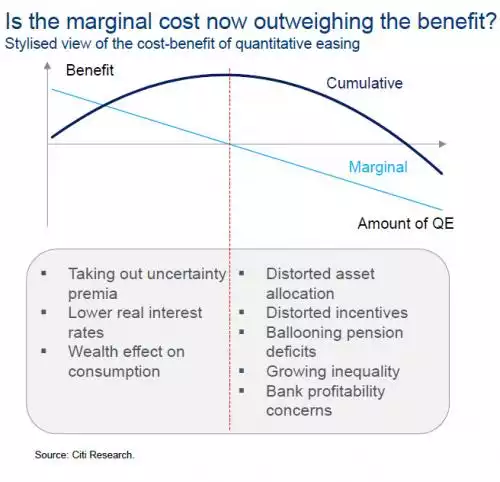

Citi quite rightly ask the question of whether the cost of all this QE is outweighing the benefits and produced the neat graphic below that clearly answers the question. Let’s hope the RBA never follow this ‘folly’.