IMF – World record debt’s ‘bright’ and ‘dark’ sides

News

|

Posted 11/11/2019

|

18296

Whilst you most likely did not read it anywhere in the mainstream press, the IMF’s new chief, Kristalina Georgieva, warned over the weekend that “Global debt—both public and private—has reached an all-time high of $188 trillion. This amounts to about 230 percent of world output”. That is up 15% from the previous record of $164 trillion just 3 years earlier in 2016.

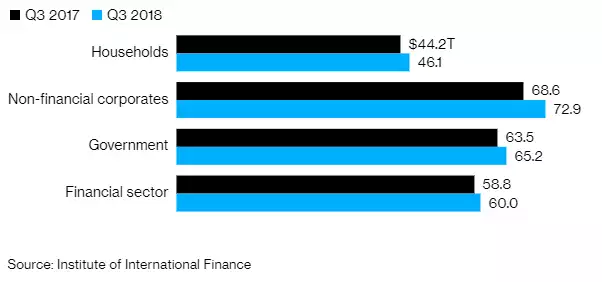

This differs significantly from the IIF’s (Institute of International Finance) figures of $244 trillion earlier this year with that figure being an incredible 318% of GDP. The breakup of the IIF’s figure shows $60 trillion of that $244t was the financial sector which is often excluded from such figures and that might explain the difference (which is close to $244-$188).

Addressing the IMF’s 20th Annual Research Conference in Washington, her talk was titled How to Use Debt Wisely. Georgieva explained there is “The bright side of debt” and “The dark side of debt”. She explains the former as “Simply put, they allow us to do something now and pay for it later, when we have more income.” Note the ‘when’ implies certainty in that proposition and hence the need for full faith in the underlying asset being worth more in the future, particularly in the case of all the corporate and private debt, and of course for public debt that somehow these decades of deficits will miraculously reverse and the reality of the unfunded liabilities won’t materialise. The latter is mathematically impossible.

And in so addressing the dark side she starts with the salient reminder “And yet, history tells us about the darker side of debt. Think of the devastating effects of unsustainable credit booms, including in the run-up to the global financial crisis.”

She goes on to explain:

“Addressing these issues is more important than ever, because the current level of record-high debt poses risks to economic and financial stability.

Remember: the buildup of public debt has a lot to do with the policy response to the 2008 financial crisis—when private debt moved to public balance sheets, especially in advanced economies.

Recent IMF staff research [ii] shows that direct public support to financial institutions alone amounted to $1.6 trillion during the 2008 crisis.

In developing countries, the buildup reflects a broader range of factors—from sharp declines in commodity prices, to natural disasters and civil conflict, to high investment spending on projects that were not productive.

The bottom line is that high debt burdens have left many governments, companies, and households vulnerable to a sudden tightening of financial conditions.

Yes, global financial conditions have remained easy, in part because interest rates are low for longer than expected in advanced economies. But the world is also facing increased uncertainty—driven by trade tensions, Brexit, and geopolitical risks.

If investor sentiment were to shift, the more vulnerable borrowers could face financial tightening and higher interest costs—and it would become more difficult to repay or roll over debt. This, in turn, could amplify market corrections and intensify capital outflows from emerging markets.

Of course, high debt is not just a risk to financial stability; it can also become a drag on growth and development efforts.

In low-income countries, high debt burdens could jeopardize development goals as governments spend more on debt service and less on infrastructure, health, and education. We estimate that 43 percent of low-income countries are either at high risk of falling into debt distress or are already in distress.”

With the relaunch of ‘notQE’ we are arguably already seeing another example of further “support of financial institutions” as the US Fed injects liquidity into the inter bank Repo market to avoid a liquidity crises.

What the IMF are trying to warn is that the world needs to understand that the ‘bright side’ of debt is certainly effective at the beginning of a cycle but we have been collectively piling into more and more debt very very late in the cycle on the basis that things will just keep going up. History says they never do. The fall back of governments taking on failed debt is looking more precarious as they are, simply, not able to.

“Public debt in advanced economies is at levels not seen since the Second World War. Emerging market public debt is at levels last seen during the 1980s debt crisis. And low-income countries have seen sharp increases in their debt burdens over the past five years.”

Hence why the G20 countries agreed on bail-in laws in 2014. We remind you that our very own government quietly and deceptively brought that legislation into effect here (as we reported here). If you haven’t read that article, you must. Combined with the cash ban, one can easily see an agenda here that should have you thinking about where you want to store your wealth.