Lessons from the 70’s and why now is different

News

|

Posted 22/07/2021

|

7272

Older readers will remember the 70’s well. It was a decade of extraordinary inflation and economic hardship. Investopedia gives an excellent precis:

“It's the 1970s, and the stock market is a mess. It has lost nearly 50% over a 20-month period, and for close to a decade few people want anything to do with stocks.? Economic growth is weak, which results in rising unemployment that eventually reaches double-digits.

The easy-money policies of the American central bank—designed to generate full employment by the early 1970s—also resulted in high inflation.? The central bank (once under different leadership) would later reverse its policies, raising interest rates to some 20%—a number once considered usurious.? For interest-sensitive industries, such as housing and cars, rising interest rates cause a calamity. With interest rates skyrocketing, many people are priced out of new cars and homes.?

Interest Rate Casualties

This is the gruesome story of the great inflation of the 1970s, which began in late 1972 and didn't end until the early 1980s. ? In his book, "Stocks for the Long Run: A Guide for Long-Term Growth" (1994), Wharton professor Jeremy Siegel, called it "the greatest failure of American macroeconomic policy in the postwar period."

The great inflation was blamed on oil prices, currency speculators, greedy businessmen, and avaricious union leaders. However, it is clear that monetary policies, which financed massive budget deficits and were supported by political leaders, were the cause. This mess was proof of what Milton Friedman said in his book, Money Mischief: Episodes in Monetary History: Inflation is always "a monetary phenomenon."? The great inflation and the recession that followed wrecked many businesses and hurt countless individuals.? Interestingly, John Connally, the Nixon-installed Treasury Secretary who did not have formal economics training, later declared personal bankruptcy.

Yet these unusually bad economic times were preceded by a period in which the economy boomed, or appeared to boom. Many Americans were awed by the temporarily low unemployment and strong growth numbers of 1972.

? Therefore, they overwhelmingly re-elected their Republican president, Richard Nixon, and their democratic Congress, in 1972; Nixon, the Congress, and the Federal Reserve eventually ended up failing them.”

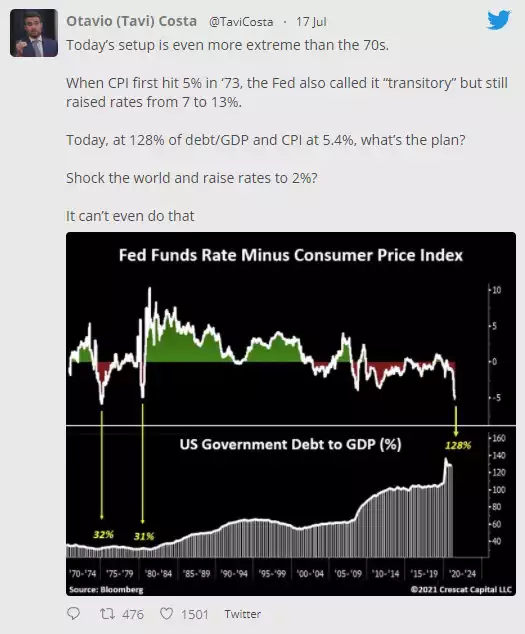

Sound and feel a little familiar? In the 70’s they were calling inflation ‘transitory’ too. The biggest difference however is the amount of debt they started with then compared to that now. The following tweet from Crescat’s Otavio Costa paints a graphic reminder:

The 70’s were also a wild period for commodities and precious metals in particular. Part of Nixon losing control was his huge deficit spending saw a loss of confidence in the US dollar which at the time was convertible for gold under the Bretton Woods gold standard. In 1971 he declared “I have directed Secretary Connally to suspend temporarily the convertibility of the dollar into gold” to stop the torrent of gold leaving the US. In a few weeks’ time we will see the 50th anniversary of this momentous event. It would be fair to say we are only getting further and further away from any end to this “temporary” suspension as the current Fed and US Government are pumping new Fiat currency into the system at a pace that would make Nixon’s jaw drop….

Set at $35/oz the gold price was then set free and reached $178 when it was again legal for Americans to own and hold gold privately in 1975. By the end of the decade gold peaked at $680/oz, a 1840% increase from the time the US dollar became pure Fiat (backed by nothing but the promise of the US government) or 280% from the time American’s could own it themselves. Silver was more spectacular going from $1.80/oz in 1970 or $4.50/oz in 1975 to $37/oz in 1980, a 1140% and 720% gain respectively.

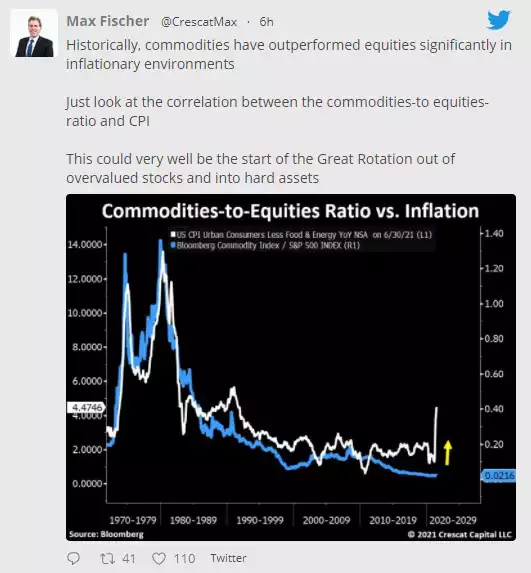

The following tweet from Crescat’s Max Fischer cannot be ignored:

Great credit cycles, as this started in 1971, never last for ever. Human greed and hubris will always see them fail. Maybe the most telling part of today’s piece is that stark contrast of the amount of debt now compared to the 70’s. There appears no orderly exit and maybe, just maybe, the “temporary” window of a Fiat system is forced shut.