WGC – 2019 Gold Demand and Supply Report

News

|

Posted 31/01/2020

|

16753

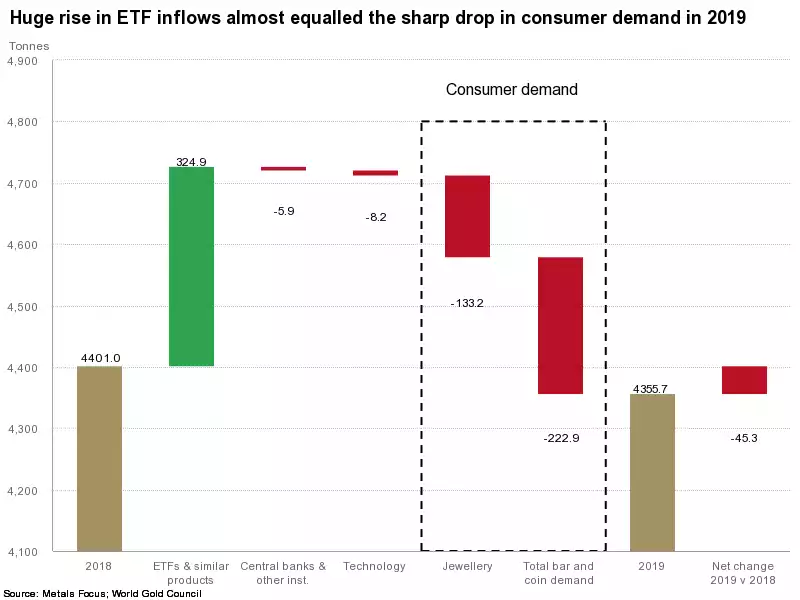

Yesterday the World Gold Council released their latest report including Q4 and a summary of all of 2019 demand and supply. In essence gold demand declined by 1% over 2018 to 4,336 tonne but with big moves behind that number and it was a year of two halves. The strong price growth in the second half saw the selective ‘buy low’ Chinese and Indian consumer markets (collectively accounting for 80% of this market move) sharply decline by 10% (19% just in Q4), exacerbated by weaker economies in each. This was offset almost entirely by strong inflows into ETF’s and central banks. Notably too, and particularly in the context of strong price growth, mining supply dropped for the first time in 10 years.

From WGC:

“Highlights

Total fourth quarter demand fell 19% y-o-y to 1,045.2t. Two main contributors to the y-o-y drop were jewellery and physical bar demand, both of which reacted to the elevated gold price. In US dollar value terms, the decline in Q4 demand was much shallower – down just 3% to US$49.7bn.

Inflows into global gold-backed ETFs and similar products pushed total holdings to a record year-end total of 2885.5t. Holdings grew by 401.1t over the year, with 26.8t added in Q4. Inflows were heavily concentrated in Q3 as the US dollar gold price rallied to a six-year high.

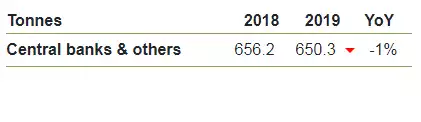

Central banks were net buyers for a 10th consecutive year: global reserves grew by 650.3t (-1% y-o-y), the second highest annual total for 50 years. Purchasing in Q4 of 109.6t was 34% lower y-o-y, although this was partly a reflection of the sheer scale of buying in 2018.

China and India held sway over global consumer demand. Together, the two gold consuming giants accounted for 80% of the y-o-y decline in Q4 jewellery and retail investment demand. High gold prices and a softer economic environment were the main culprits.

Technology saw modest declines throughout the year, although electronics demand staged a minor recovery in Q4.

Total annual gold supply edged up 2% to 4,776.1t. An 11% jump in recycling was the main reason for the increase, as consumers capitalised on the sharp rise in the gold price in the second half of the year. Annual mine production was marginally lower at 3,463.7t – the first annual decline for more than 10 years.

The gold price averaged US$1,481/oz in Q4. This was the highest average price since Q1 2013. Although the price remained below the Q3 high, it was well supported. And gold priced in various currencies – including euros, Indian rupees and Turkish lira – hit their highest levels in history.”

By Sector the highlights were:

Jewellery

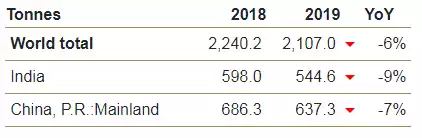

- The steep rise in the gold price in the second half of the year cut global jewellery demand. Annual volumes fell 6% to 2,107t

- Fourth quarter jewellery demand sank to its lowest since 2011 – down 10% y-o-y to 584.5t

- Weakness in India and China explained much of the drop in global volumes

- By contrast, the value of gold jewellery demand increased: the annual US dollar value was its highest for five years at US$94.3bn (+3%), with Q4 growing 9% to US$27.8bn.

Investment

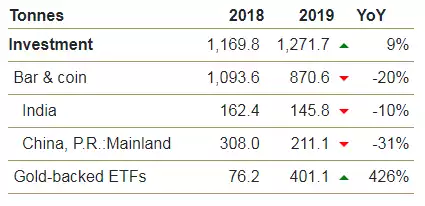

- Growth in annual investment demand was fuelled by ETF inflows, while bar and coin demand was contrastingly weak

- Gold’s price rise had a mixed impact on investment: bar and coin investors took profits, while momentum buying contributed to inflows into gold-backed ETFs

- Low interest rates and geopolitical uncertainty pushed holdings of gold-backed ETFs to record highs of 2,905.9t during Q4

- A 10-year low in bar and coin demand owed much to steep declines in China and India.

Central Banks and other institutions

- Central bank demand totalled 650t in 2019 – the 10th consecutive year of annual net purchases

- Central banks added 650.3t to global official gold reserves in 2019, 1% lower y-o-y

- 15 central banks made net purchases of a tonne or more, highlighting continued breadth of demand

- This marks ten consecutive years of net purchases, with global official reserves now 5,000t higher than end-2009 at ~34,700t.

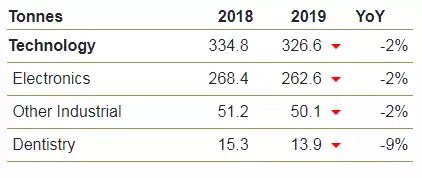

Technology

- Technology demand weakened again in 2019, but the outlook is more optimistic; 2020 should herald strong demand growth in the electronics wireless sector

- Full-year gold demand in the technology sector fell 2% y-o-y to 326.6t

- 2019 was a weak year for the whole electronics industry, and this contributed to a 2% fall in demand for gold in the sector

- However, Q4 demand showed signs of recovery, posting a 1% y-o-y increase to 68.2t. This was driven by strong growth in wireless applications as 5G installations gained traction.

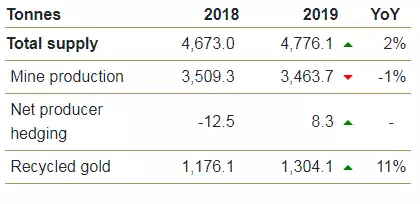

Supply

- Total supply up 2% y-o-y in 2019; recycling and producer hedging boosted by gold price performance

- Total supply increased by 2% y-o-y in 2019 to 4,776.1t, the second consecutive marginal increase in annual supply

- Mine production fell 1% to 3,464t in 2019, the first y-o-y decline in output since 2008

- Recycled gold supply rose by 11% y-o-y in response to the gold price rally that began in June.

For those interested in the break up of that decade first decline in production:

“Production growth was largely from greenfield and brownfield development. Russian gold mine production saw an 8% increase y-o-y in 2019. The ramp-up of greenfield sites – such as Natalka – and increases at several brownfield sites contributed to the growth in output. Similarly, in Australia, aggregate mine production rose by 3% y-o-y owing to higher production at several mines and the ramp up of projects such as Mount Morgans and Cadia Valley. Mine production in Turkey leapt (+66% y-o-y) due to improvements in the regulatory environment and permitting process, as well as expansion at the Copler project. In recent years the government has become more supportive towards the gold mining industry, helping to reduce the country’s trade deficit in gold. West Africa again proved to be an engine of growth for mine production. Several of the region’s nations, such as Ghana, Burkino Faso and Côte d'Ivoire, all saw increased gold production.

But this was outweighed by declines in some top producing nations. In China, the world’s largest producer, mine output fell 6% y-o-y in 2019, the third consecutive year of decline. Chinese gold production was hampered primarily by the strict environmental restrictions which have come into force in recent years. But the rate of decline has been slowing for some time as the industry becomes compliant with new regulations. In addition, the rising gold price accelerated many gold mining plans in 2019. In South Africa, industrial action in the first half of the year significantly curtailed operations. While the strikes at Beatrix, Kloof and Driefontein – which began in November 2018 – ended in April, mine production continued to feel the after-effects well into Q3. In South America, disputes between local communities and contractors – such as at Peñasquito in Mexico – also led to lower production compared to 2018. While there is a healthy pipeline of projects in this region, obtaining a social licence to operate has proved challenging.

But Indonesia had the biggest impact on global mine production in 2019 due to the activity at Grasberg. The exhaustion of higher-grade ore at Grasberg and its subsequent transition from open pit to underground mining was a constant issue throughout the year. But this drag on global production will not be felt to the same extent in 2020. The project has been ramping up its Grasberg Block Cave mine where output is expected to improve after 2020”